Acquisition Fee Explained: The Hidden Cost That Quietly Erodes Returns

Learn about Acquisition Fee for real estate investing.

When I help clients review syndication deals, acquisition fees are one of the first places I slow them down.

Not because acquisition fees are automatically bad.

But because they are easy to misunderstand, easy to underestimate, and easy to rationalize away.

I’ve seen otherwise solid deals quietly lose their edge because investors didn’t fully model what this fee actually does to their returns.

What an Acquisition Fee Really Is

An acquisition fee is a one-time payment made to the sponsor or general partner for sourcing, underwriting, and closing a property.

It is paid once.

It is usually paid at closing.

And it comes directly out of investor capital.

In practical terms, that means part of the money you invest never touches the property.

When I model deals in The World’s Greatest Real Estate Deal Analysis Spreadsheet™, I treat acquisition fees as an immediate reduction in invested equity.

Because that’s exactly what they are.

Typical Acquisition Fee Ranges

Most syndications fall into a fairly predictable range.

One percent to three percent of the purchase price is common.

Two percent is probably the most frequent number I see.

On a $10 million purchase, that’s $100,000 to $300,000 paid to the sponsor on day one.

That money is gone before the first rent check is collected.

Why Sponsors Charge Acquisition Fees

When sponsors explain their acquisition fee, they usually point to real work they’ve done.

And in many cases, that work is real.

They analyze dozens or hundreds of deals.

They build broker relationships.

They coordinate inspections, financing, attorneys, and equity investors.

When I rebuilt after bankruptcy, one of the lessons that stuck with me was this:

Effort alone does not justify compensation. Results do.

The question is not whether the sponsor worked hard.

The question is whether the value created exceeds the fee charged.

Acquisition Fees Inside Syndications

In syndications, acquisition fees are usually paid at closing from the equity raise.

That creates an important incentive problem.

Sponsors get paid whether the deal performs well or not.

That doesn’t mean the deal is bad.

But it does mean you need to look at alignment very carefully.

When sponsors also invest meaningful personal capital, I worry less.

When acquisition fees are high and sponsor co-investment is low, I start asking harder questions.

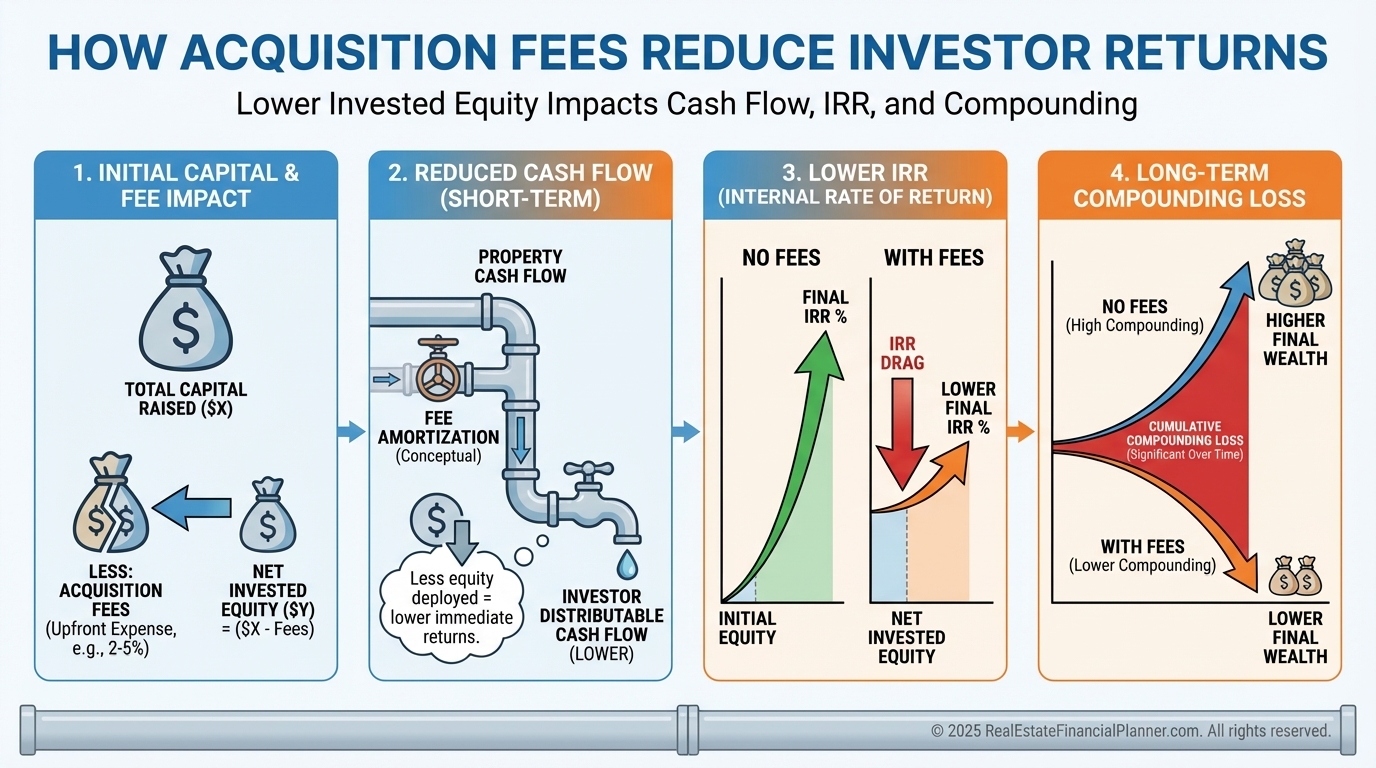

How Acquisition Fees Impact Returns

This is where most investors underestimate the damage.

Acquisition fees reduce invested equity immediately.

That lowers cash-on-cash returns, IRR, and long-term compounding.

When I run Return Quadrants™, the acquisition fee hits every quadrant except appreciation.

The shorter the hold period, the more painful the fee becomes.

Modeling Acquisition Fees Correctly

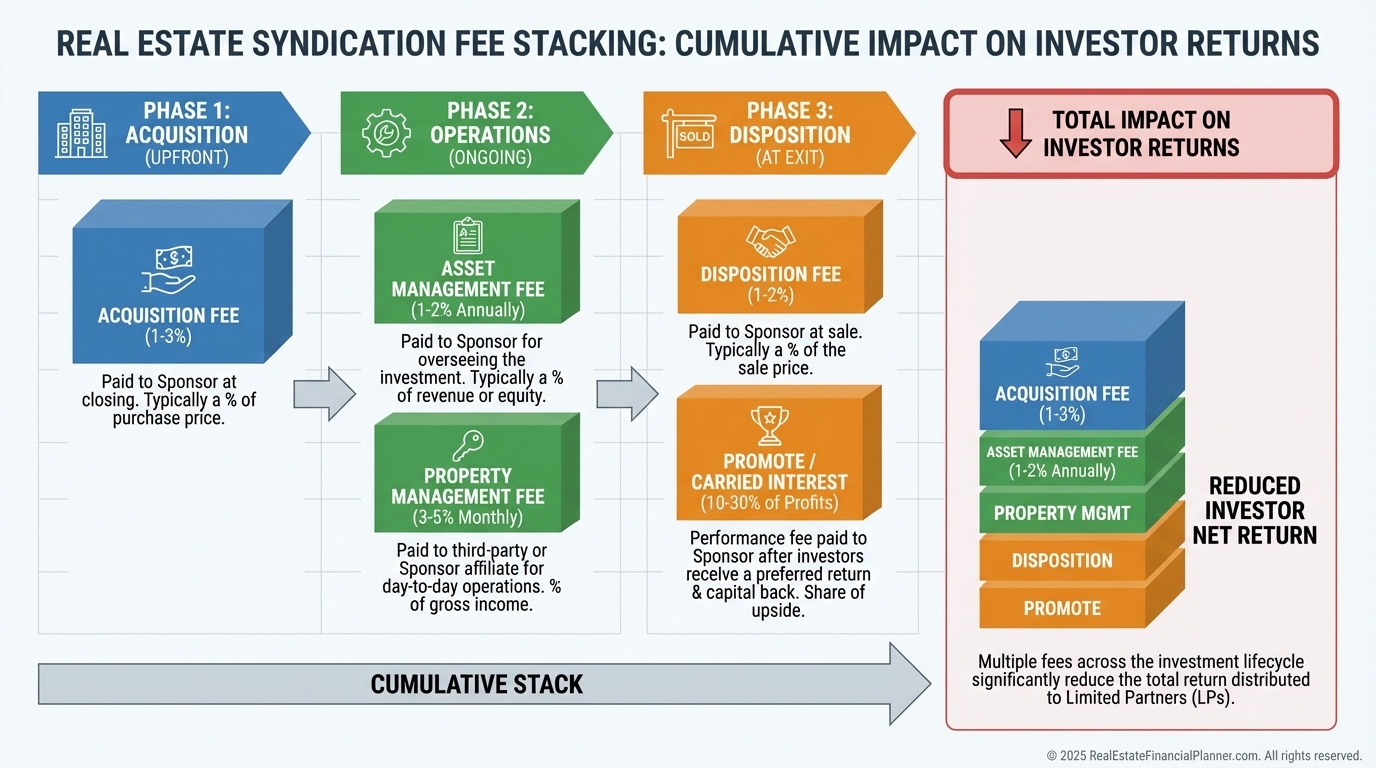

I never look at acquisition fees in isolation.

I model the entire fee stack.

A low acquisition fee can still be expensive if everything else is layered aggressively.

This is why spreadsheets beat gut feelings every time.

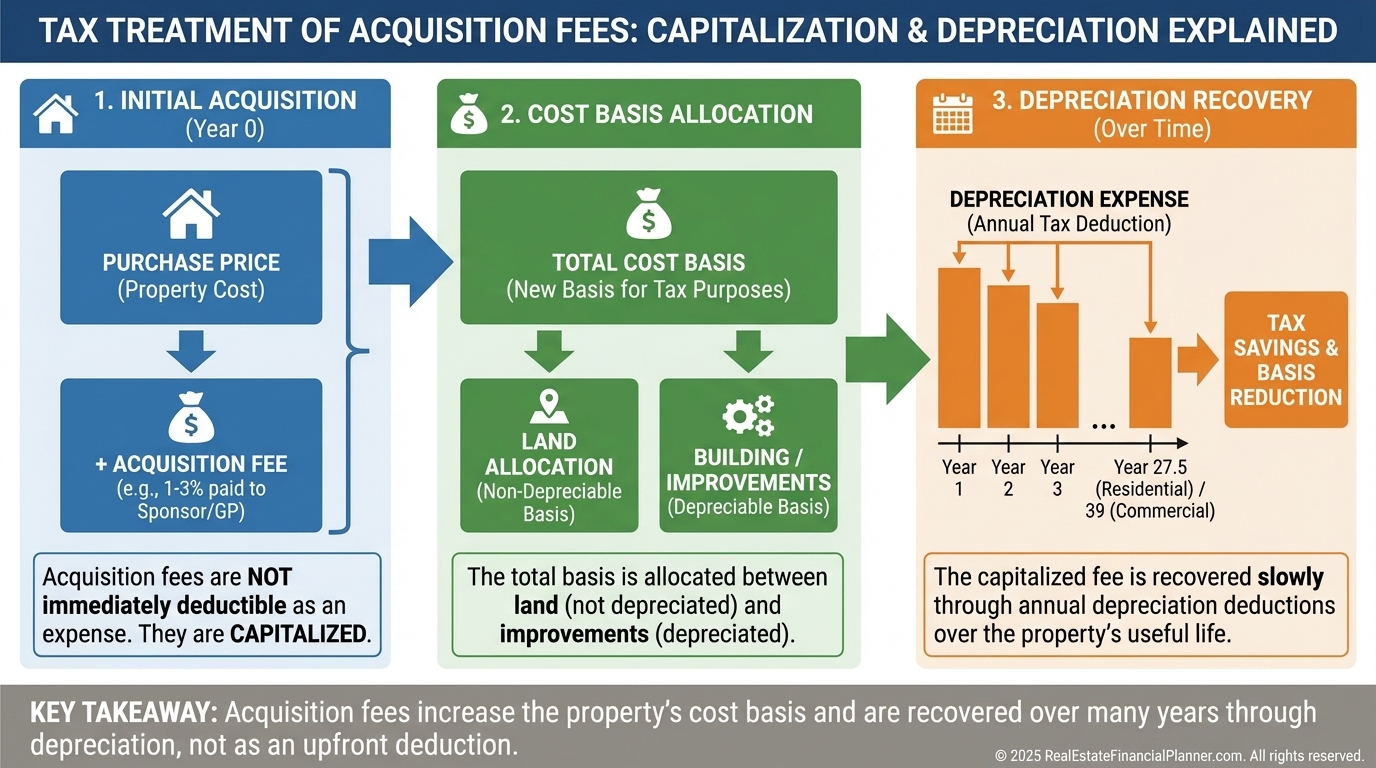

Tax Treatment of Acquisition Fees

Acquisition fees are typically capitalized.

That means no immediate deduction.

Instead, they are recovered slowly through depreciation.

From an after-tax perspective, this makes acquisition fees more expensive than they first appear.

Red Flags I Warn Clients About

Over the years, a few patterns keep repeating.

Acquisition fees above three percent without exceptional justification.

Fees charged on the sponsor’s own invested capital.

Vague disclosures.

Resistance to basic questions.

When sponsors can’t clearly explain how they get paid, I stop listening.

The Right Way to Think About Acquisition Fees

Acquisition fees are not automatically bad.

They are a trade.

You are paying for sourcing, structuring, and execution.

The only thing that matters is what is left after all fees.

Net returns.

Net cash flow.

Net wealth growth.

When I analyze deals, I don’t ask, “Is the fee reasonable?”

I ask, “Is this still a great deal after the fee?”

That mindset has saved my clients from more bad investments than any rule of thumb ever could.