Earnest Money Explained: How One Deposit Can Protect—or Destroy—Your Real Estate Deal

Learn about Earnest Money for real estate investing.

When I help clients buy rental properties, earnest money is one of the first things I explain carefully.

Not because it’s complicated—but because misunderstandings here cost real money.

I’ve seen investors lose deals they should have won.

I’ve also seen investors lose earnest money they never needed to risk.

Earnest money isn’t just a formality.

It’s a leverage point, a signaling mechanism, and a risk-management decision.

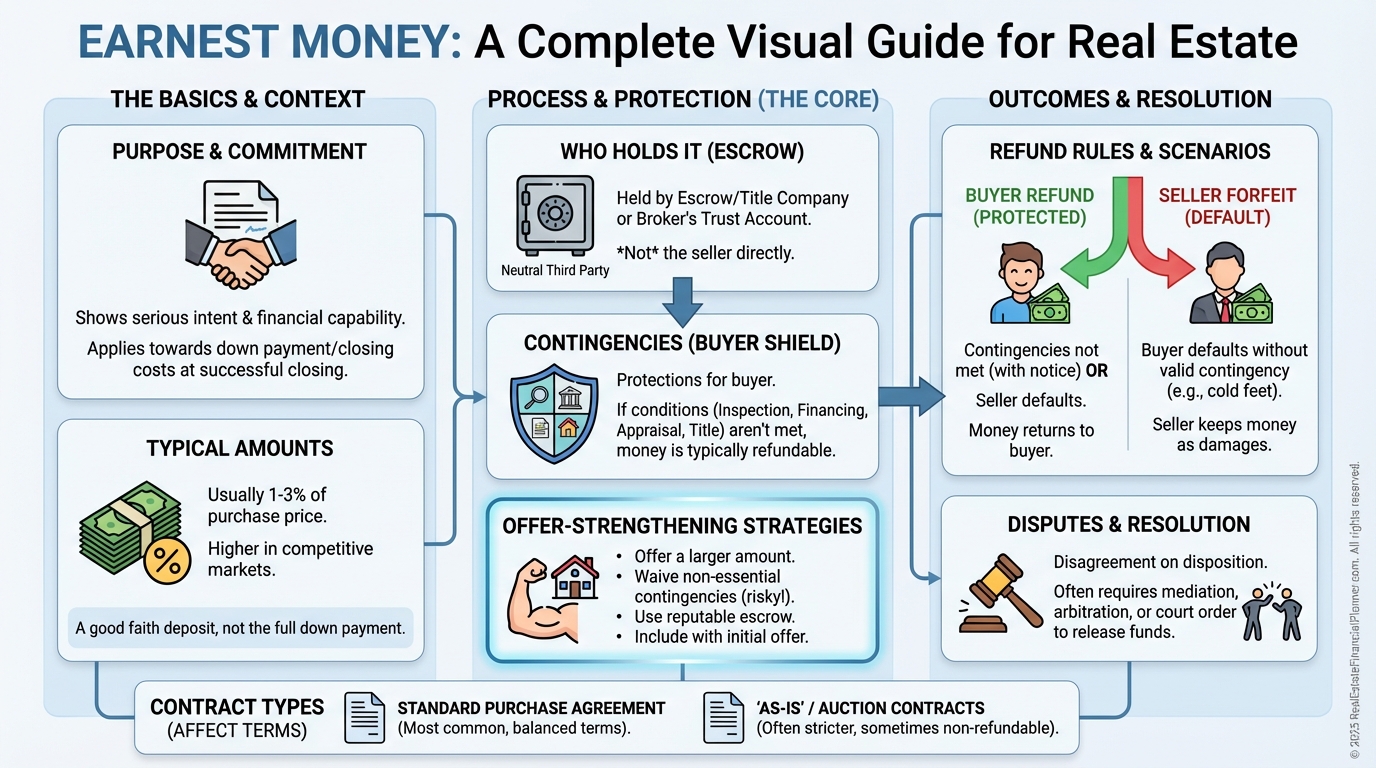

What Earnest Money Really Is

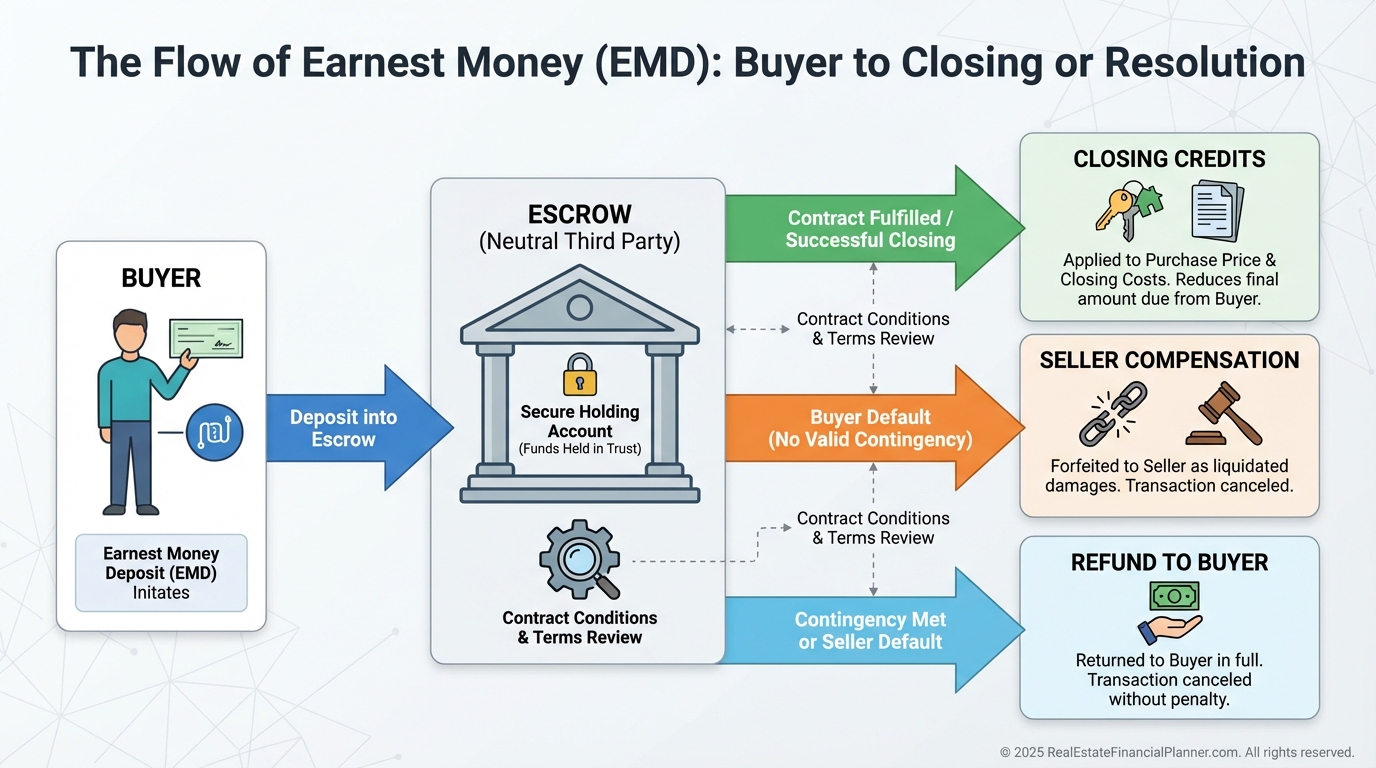

Earnest money is a deposit you make after your offer is accepted to show the seller you’re acting in good faith.

It’s typically delivered within a few business days and held by a neutral third party like a title company, broker, or attorney.

This money does not disappear.

If you close, it is credited toward your down payment or closing costs.

But until then, it sits in escrow as a performance bond.

For sellers, earnest money compensates them if you fail to perform.

For you, it creates discipline and deadlines.

It also reveals how well you understand contracts.

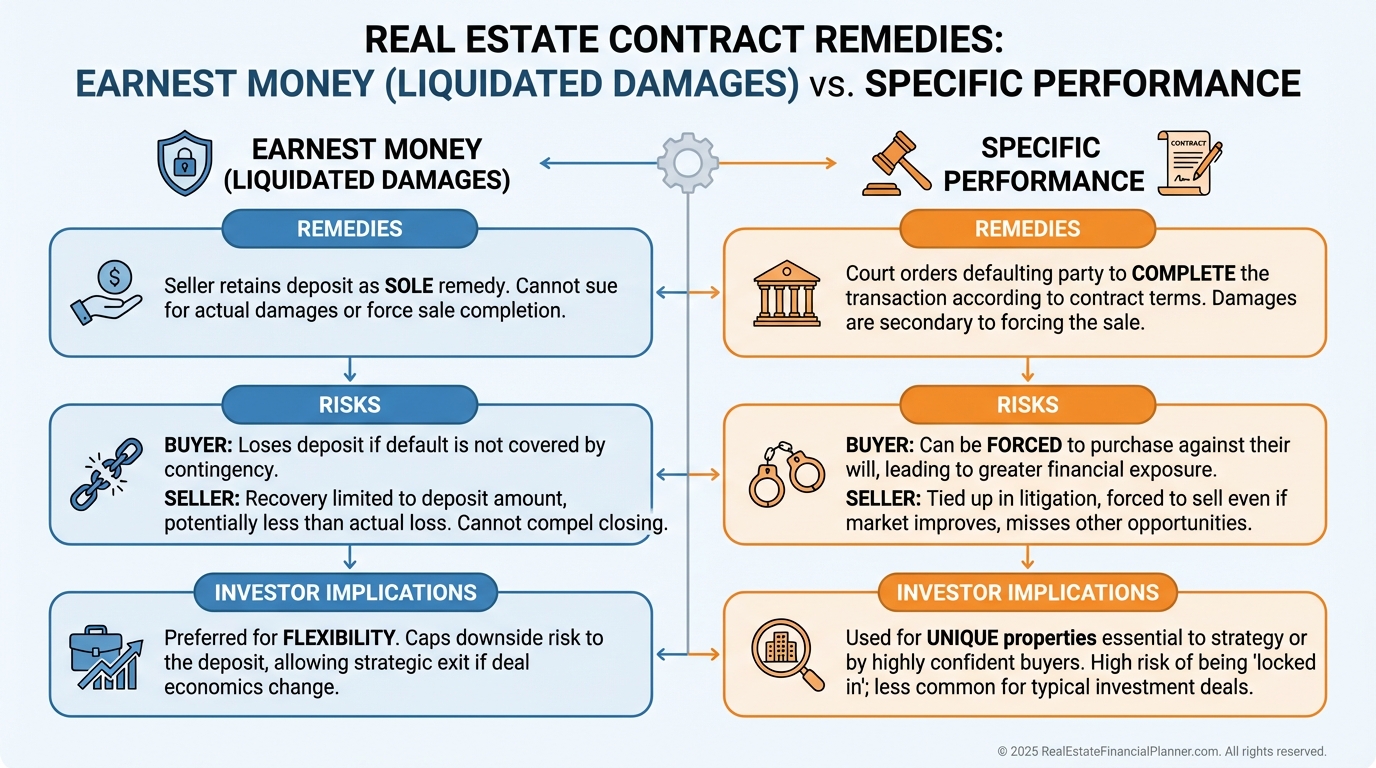

Earnest Money Versus Specific Performance

This distinction matters far more than most investors realize.

An earnest money contract—also called a liquidated damages contract—limits the seller’s remedy if you default.

If you fail to perform, the seller keeps the earnest money.

That’s it.

A specific performance contract is different.

It allows the non-defaulting party to force the other side to close.

If you agree to specific performance as the buyer, a seller could sue to force you to purchase the property—not just keep your deposit.

Most investor contracts are structured so your risk is capped at earnest money, while the seller is bound by specific performance.

That asymmetry protects you—if you understand it.

Is Earnest Money Required?

Technically, no.

Practically, yes.

Most sellers expect it.

And in many contracts, earnest money serves as legal consideration.

No earnest money often means no deal—especially in competitive markets.

I remind clients that earnest money is not an added expense.

It’s money you were already planning to bring to closing.

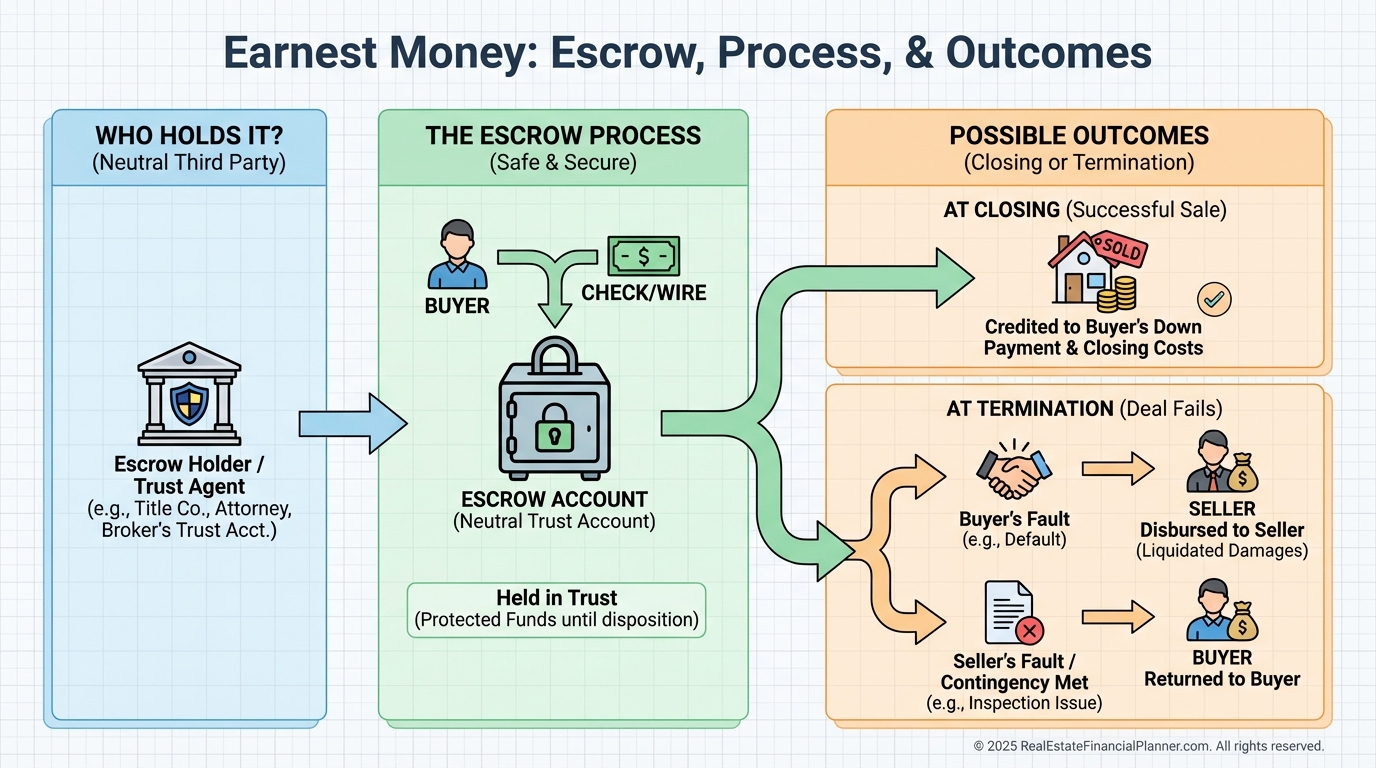

Who Holds Earnest Money—and Why It Matters

Earnest money should be held by a neutral, reputable third party.

Usually a title company.

Sometimes a broker or attorney.

Depending on how the deal ends, earnest money can be:

Applied to your closing costs.

Returned to you.

Released to the seller.

Split as part of a negotiated settlement.

Always get a receipt.

Always confirm delivery deadlines.

Miss that deadline, and you may be in default before inspections even begin.

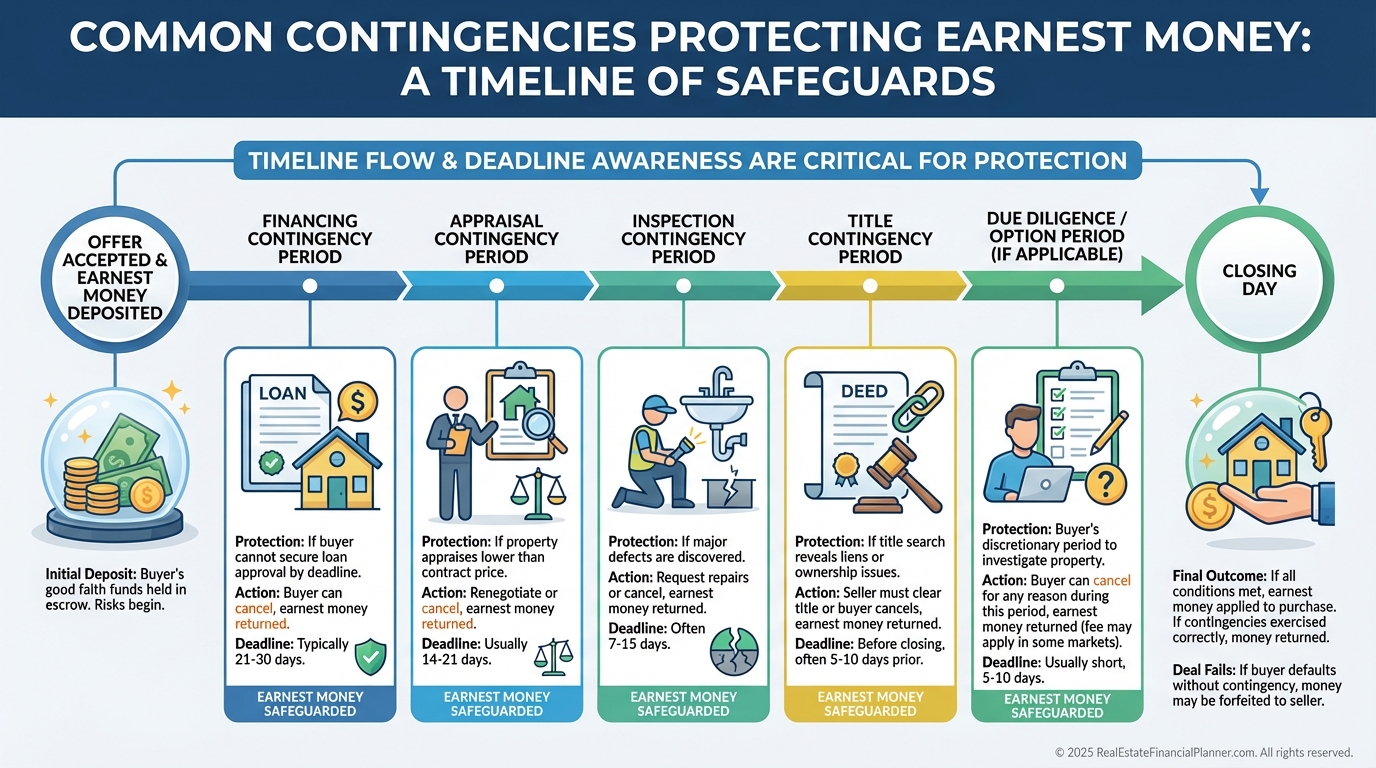

When You Get Your Earnest Money Back

Earnest money is refundable only if you terminate properly under a valid contingency.

That means timing matters more than intention.

Typical contingencies include:

Miss a deadline—even by one day—and you may lose protection.

I’ve seen investors “do everything right” and still lose earnest money because they failed to send written notice on time.

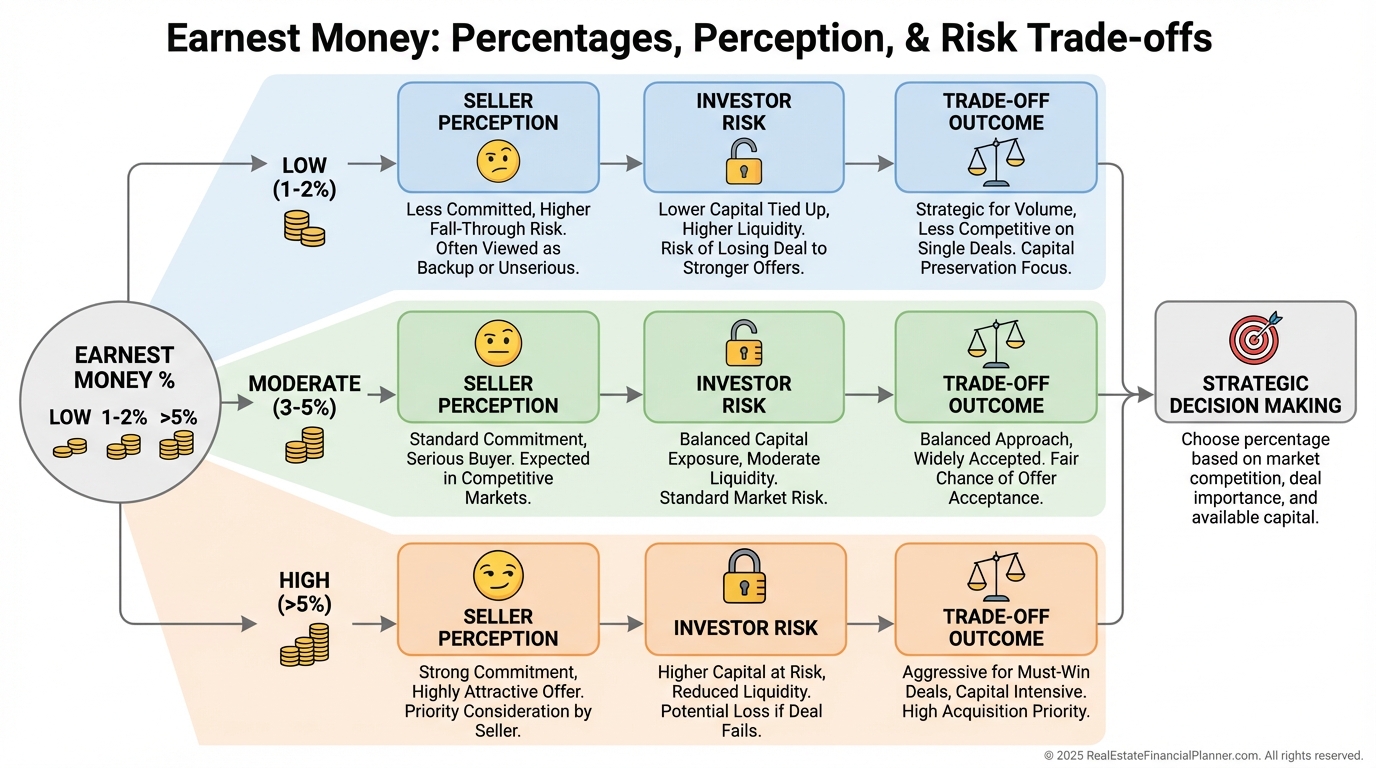

How Much Earnest Money Should You Put Down?

One percent of the purchase price is common.

Less may weaken your offer.

More may strengthen it—but only marginally unless contingencies are waived.

Remember: earnest money increases risk, not return.

It only improves offer optics.

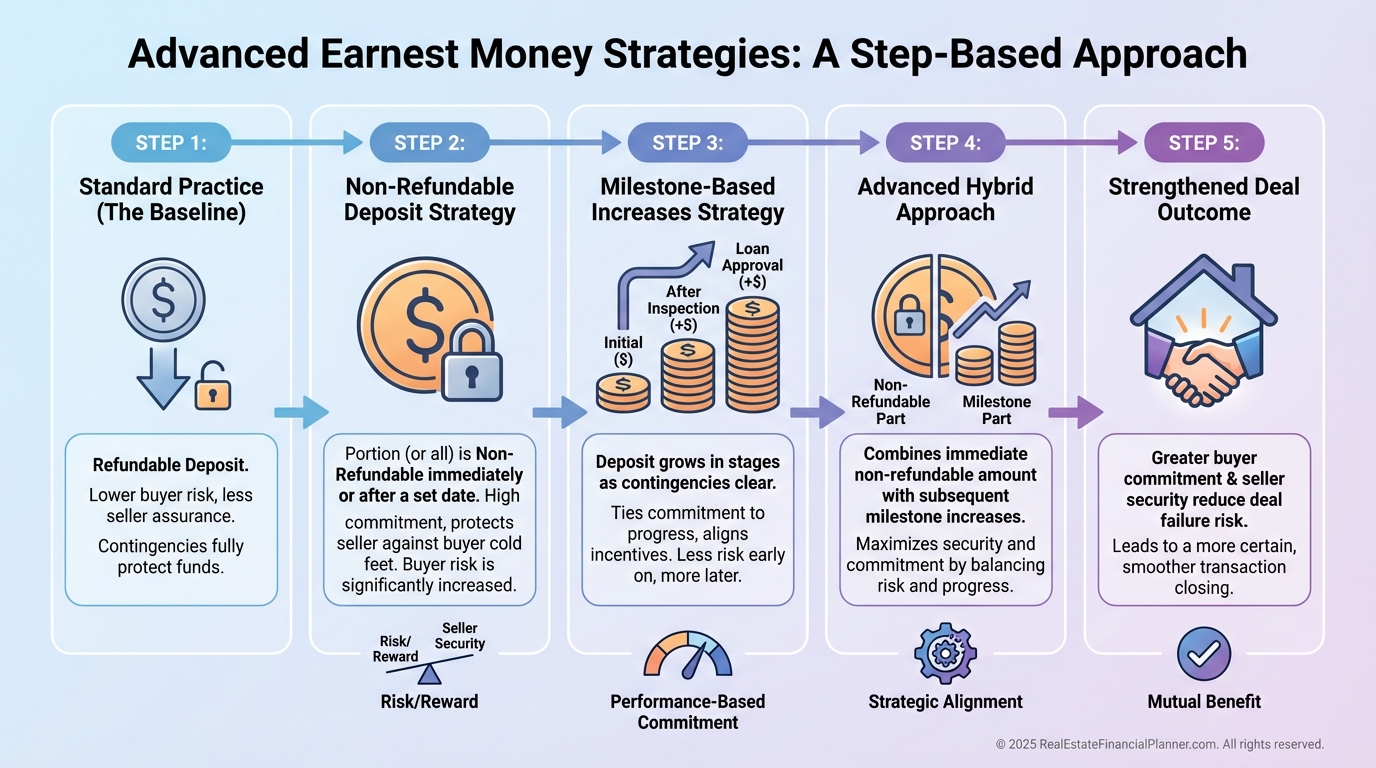

Using Earnest Money to Strengthen Offers

If you want earnest money to matter, structure it intentionally.

You can make portions non-refundable.

You can add additional earnest money after inspections or appraisal.

Each step increases risk—but only after uncertainty decreases.

That’s how sophisticated investors think.

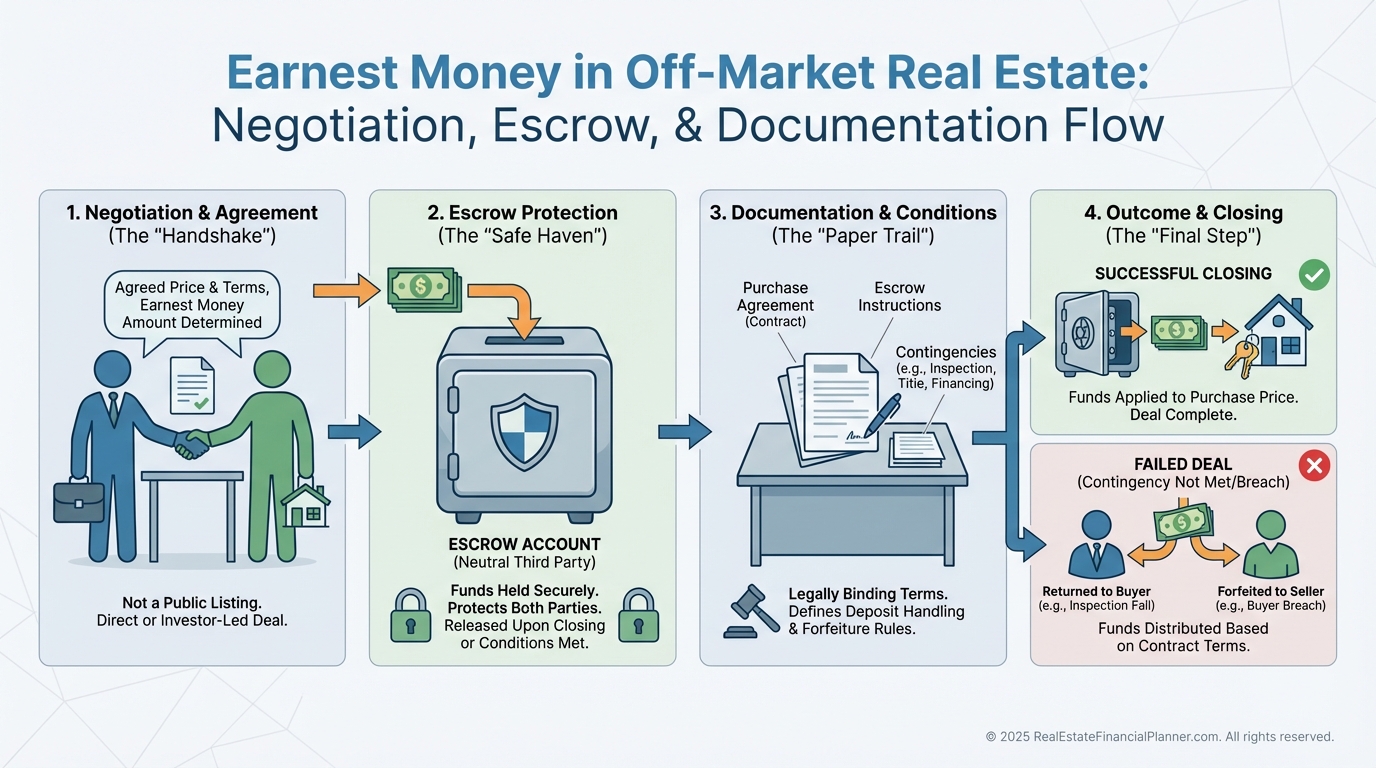

Earnest Money in Off-Market Deals

Off-market deals have no MLS guidance.

Everything is negotiable.

I usually push for lower earnest money and insist on third-party escrow—especially as amounts increase.

Never let the seller hold it directly unless the amount is trivial and trust is absolute.

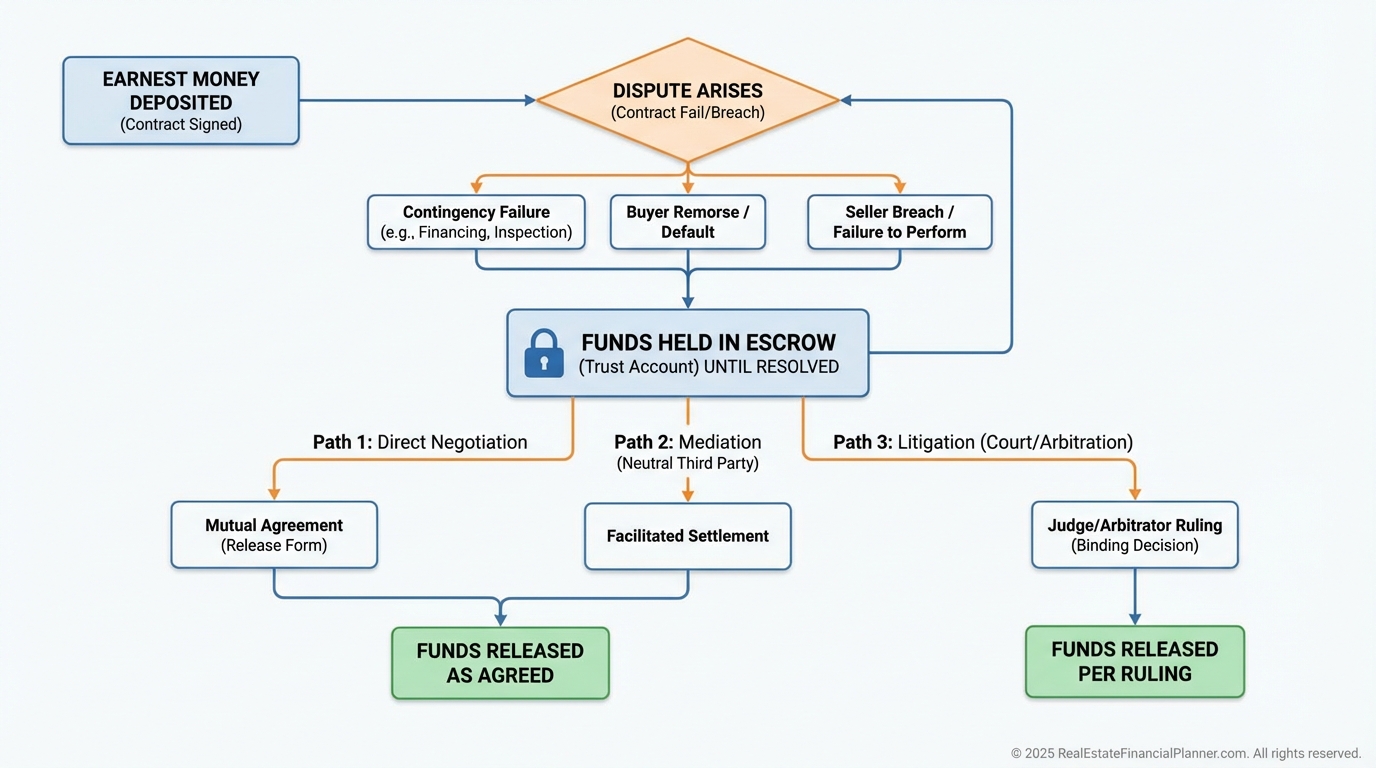

What Happens During an Earnest Money Dispute

Disputes freeze capital.

The escrow holder won’t release funds until both parties agree or a legal process resolves it.

That money becomes unusable for future deals.

Sometimes the legal cost exceeds the deposit.

That’s why clarity up front beats enforcement later.

Final Investor Perspective

Earnest money is not about proving seriousness.

It’s about managing downside risk.

When I rebuilt after bankruptcy, I treated earnest money like any other capital allocation decision—measured, intentional, and deadline-driven.

That mindset protects deals long before closing day.