Commercial Financing Explained: How Investors Actually Get Large Deals Funded

Learn about Commercial Financing for real estate investing.

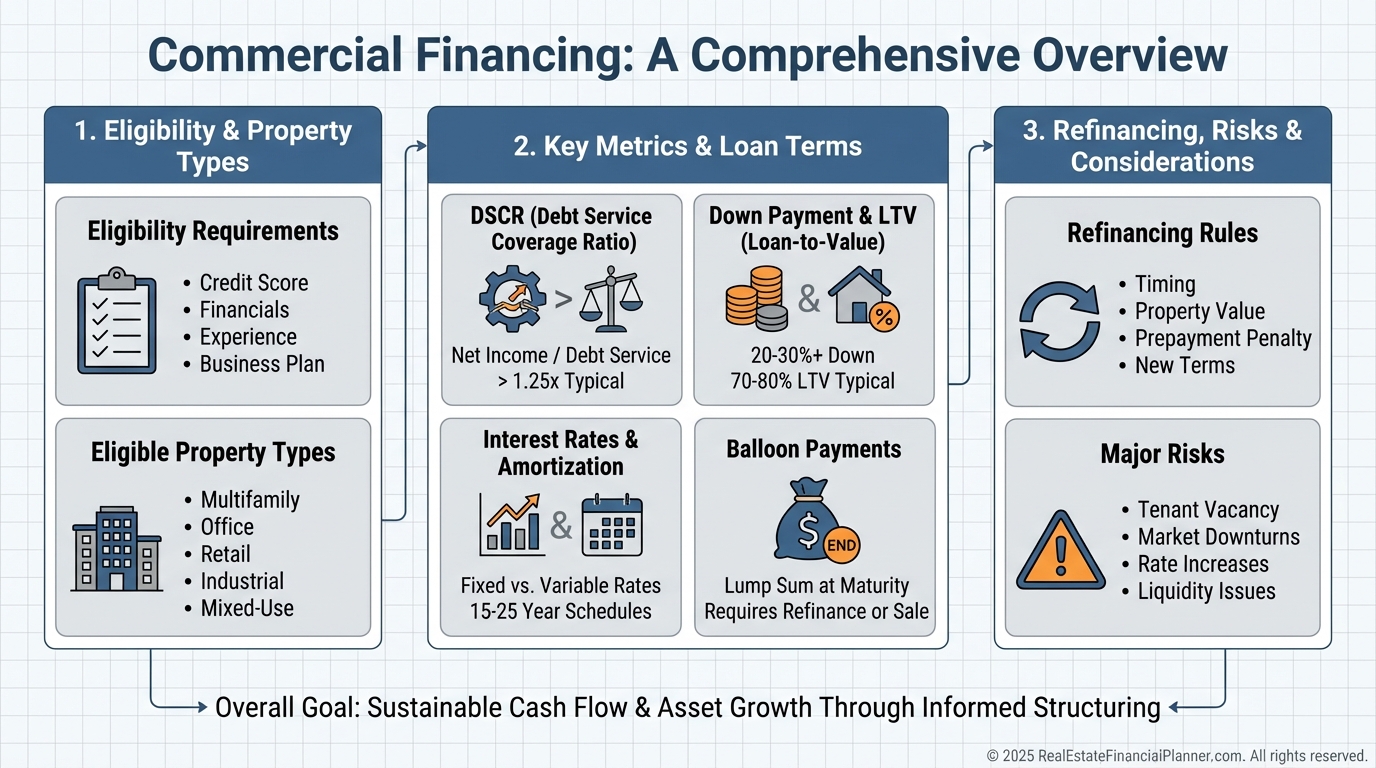

Commercial Financing Overview

Commercial financing is where real estate investing starts to feel like real business lending.

When I help clients move from one- to four-unit properties into five-plus units or mixed-use buildings, this is usually where assumptions break down.

Commercial loans are not just “bigger residential loans.”

They are underwritten, priced, and structured around risk in very different ways.

If you do not understand those differences, you can accidentally buy a property that looks great on paper but quietly sets you up for refinancing stress, forced sales, or permanent cash flow drag.

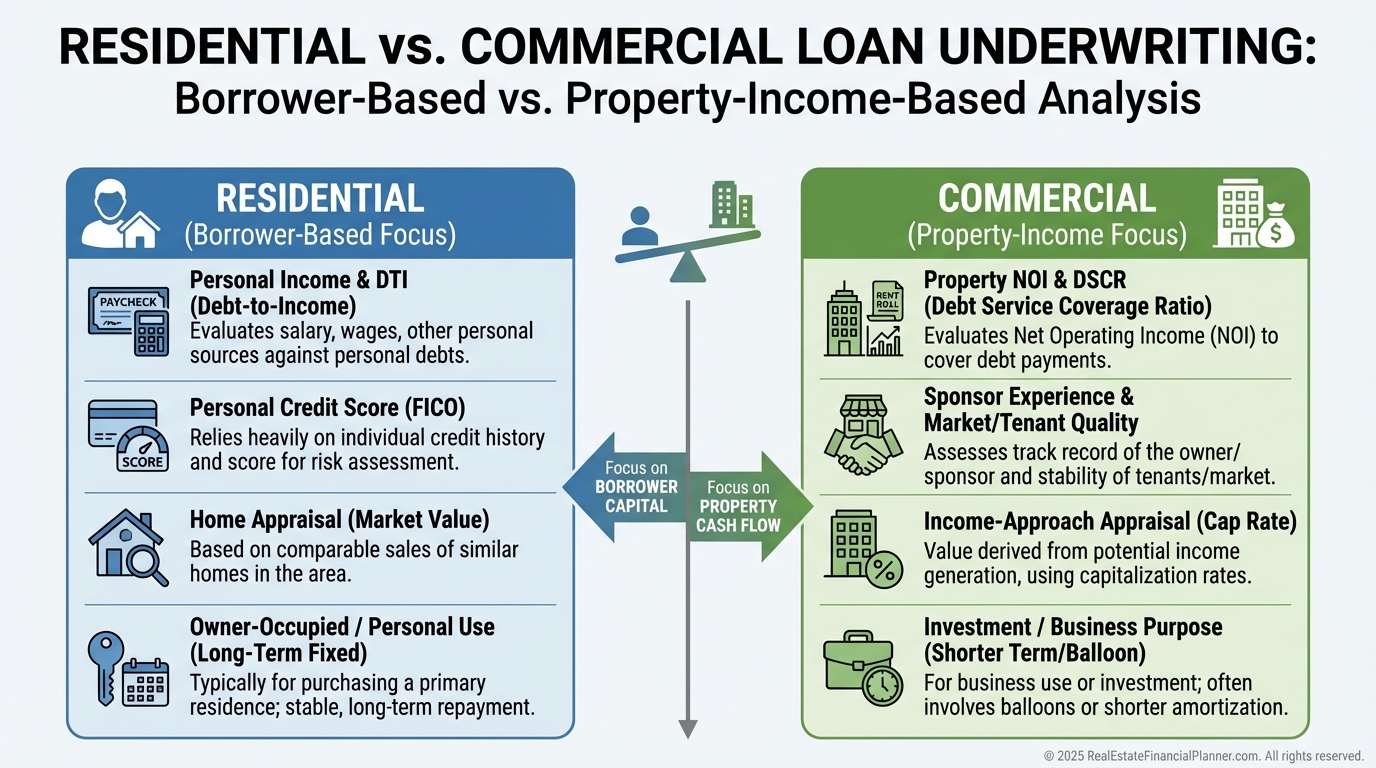

What Commercial Financing Is Really Based On

Residential loans focus heavily on you.

Commercial loans focus heavily on the property.

That shift changes almost everything.

The lender is primarily asking one question:

“Does this property reliably produce enough income to pay us back with a margin of safety?”

Your income, assets, and experience still matter, but they support the deal rather than define it.

Residential vs Commercial Loan Focus

Eligibility and Underwriting Reality

Most commercial lenders want to see a credit score of around 660 or higher.

More importantly, they want clean, well-documented financials.

When I rebuilt after bankruptcy, this was one of the first lessons I learned the hard way: commercial lenders do not guess.

They verify.

Sloppy documentation slows deals or kills them entirely.

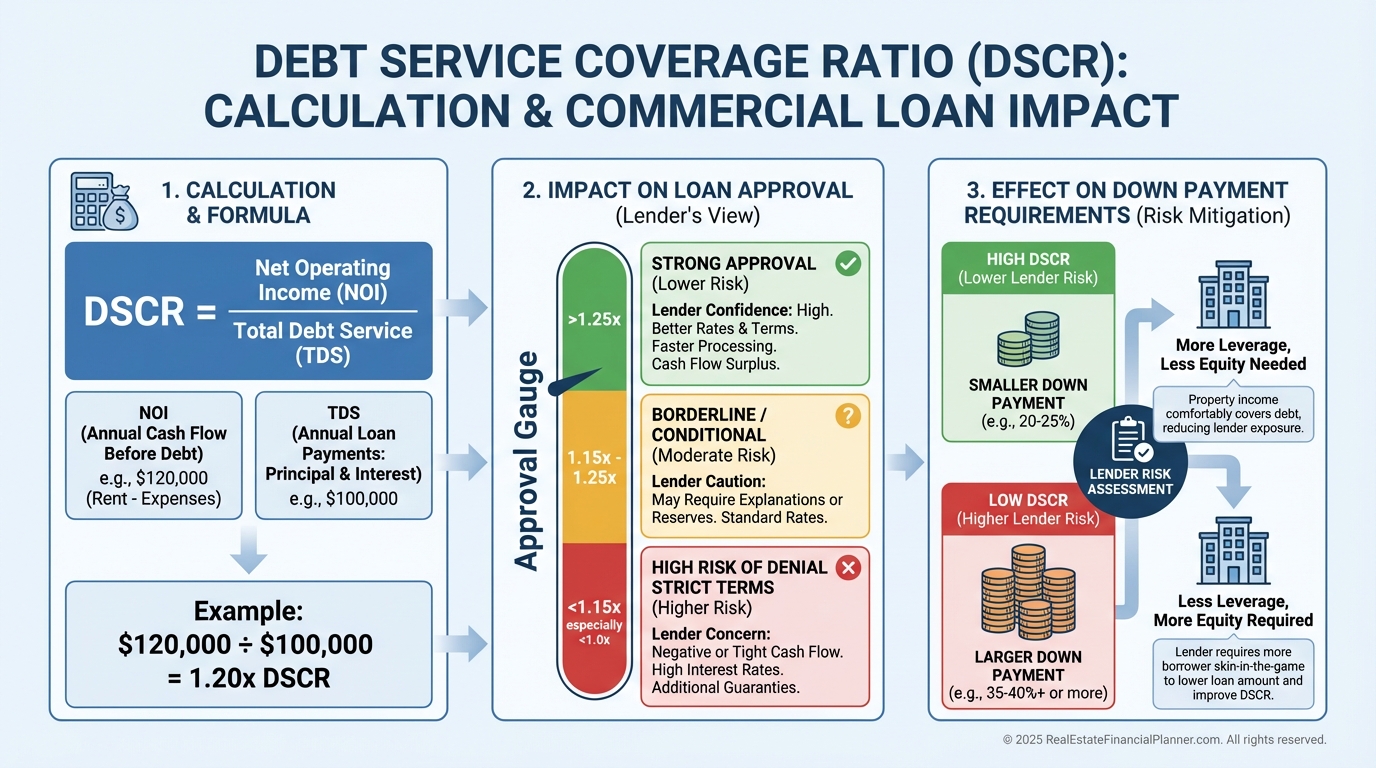

DSCR: The Gatekeeper Metric

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) is the single most important number in commercial financing.

Most lenders want a DSCR of at least 1.25.

That means the property must generate twenty-five percent more income than required to service the debt.

If the property does not meet that threshold, the solution is rarely creative structuring.

The solution is usually more money down.

How DSCR Controls Loan Approval

This is where many investors first feel surprised.

A deal that looks “close enough” under residential logic can require dramatically more capital under commercial rules.

Owner-Occupancy Does Not Save You Here

Commercial loans do not care if you live in the property.

There is no owner-occupancy advantage.

These loans are designed for stabilized, income-producing assets, not personal housing transitions.

Down Payments and Loan-to-Value

Commercial loans demand real equity.

Typical down payments range from twenty to thirty percent.

Riskier properties can require thirty-five percent or more.

Loan-to-value ratios are usually capped between seventy and eighty percent.

If the property, tenant mix, or market introduces additional risk, that cap drops.

I always model this upfront using conservative assumptions, because stretching to make a deal “work” at eighty percent LTV is how investors end up refinancing too soon or selling under pressure.

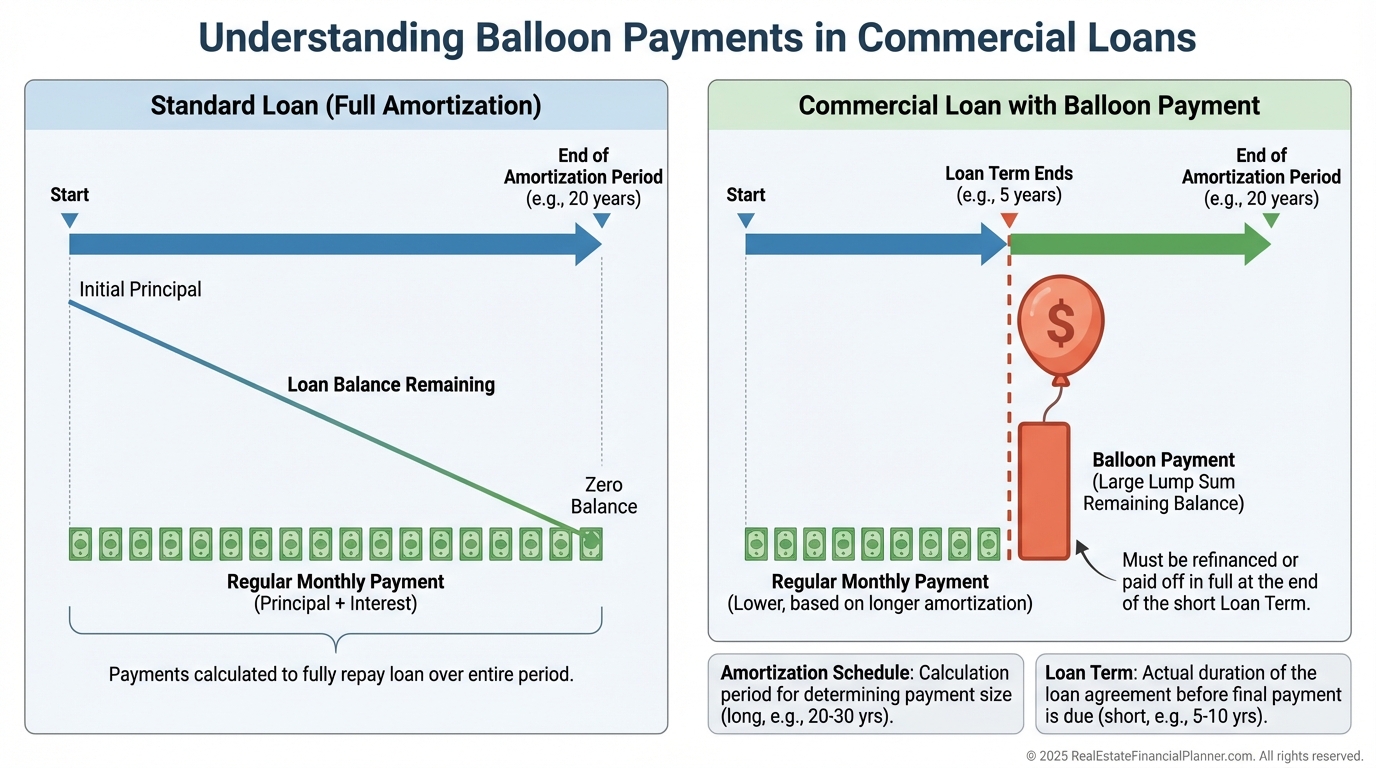

Interest Rates and Amortization Structure

Commercial rates are usually higher than residential rates.

They are also more complex.

Many loans have a short fixed-rate period followed by adjustable rates.

Most have amortization schedules of twenty to thirty years paired with five-, seven-, or ten-year terms.

That means balloon payments.

Balloon Payments Explained

Balloon payments are not inherently bad.

Ignoring them is.

Every commercial deal should be analyzed with an exit plan that assumes refinancing may be harder, slower, or more expensive than expected.

PMI, Loan Limits, and Scaling

Commercial loans do not use private mortgage insurance.

The down payment replaces that risk buffer.

There are also no government-imposed loan limits.

Loan size depends on the property, the numbers, and your ability to support the deal.

Commercial loans also do not count against residential loan limits.

This allows investors to scale portfolios strategically across financing types.

Seller Concessions and Negotiation Reality

Seller concessions exist in commercial deals, but they are not assumed.

Everything is negotiated.

Even when concessions are allowed, lenders often cap how much can be applied toward closing costs.

This is another place where I see investors miscalculate their true cash required at closing.

Waiting Periods After Financial Setbacks

Commercial lenders are often more flexible after bankruptcy or foreclosure.

Two to four years is common.

Exceptions are possible when the property cash flow is strong and your financial recovery is well documented.

This flexibility is one reason commercial financing can play a role in rebuilding strategies when used carefully.

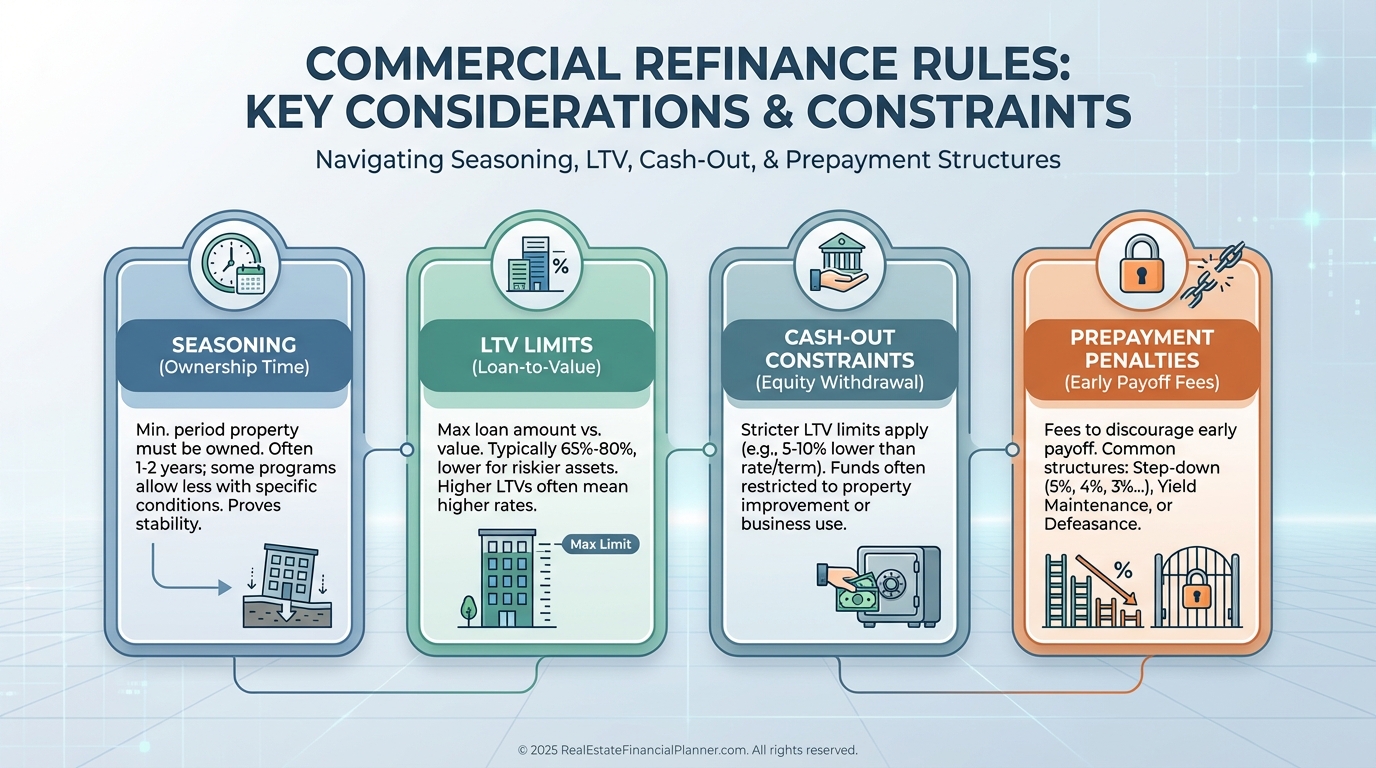

Refinancing and Prepayment Penalties

Commercial refinancing rules vary widely.

Rate-and-term refinances often require longer seasoning periods.

Cash-out refinances usually cap LTV around sixty-five to seventy percent.

Prepayment penalties are common and often overlooked.

Commercial Refinance Constraints

When I analyze these deals, I always include prepayment penalties in True Net Equity™ calculations.

Ignoring them distorts returns and exit decisions.

Entities, Guarantees, and Non-Recourse Reality

Commercial properties are often purchased in LLCs or other entities.

That does not automatically eliminate personal risk.

Most loans still require personal guarantees.

True non-recourse loans exist, but they usually require larger down payments and lower leverage.

If someone promises non-recourse with high leverage, slow down and verify everything.

Approval Is a Process, Not a Checkbox

Commercial underwriting is slower and more deliberate.

Large loans often go through loan committees.

Rent rolls, vacancy assumptions, expense ratios, and market conditions are scrutinized.

This is normal.

If a commercial lender rushes, that is usually a warning sign, not a benefit.

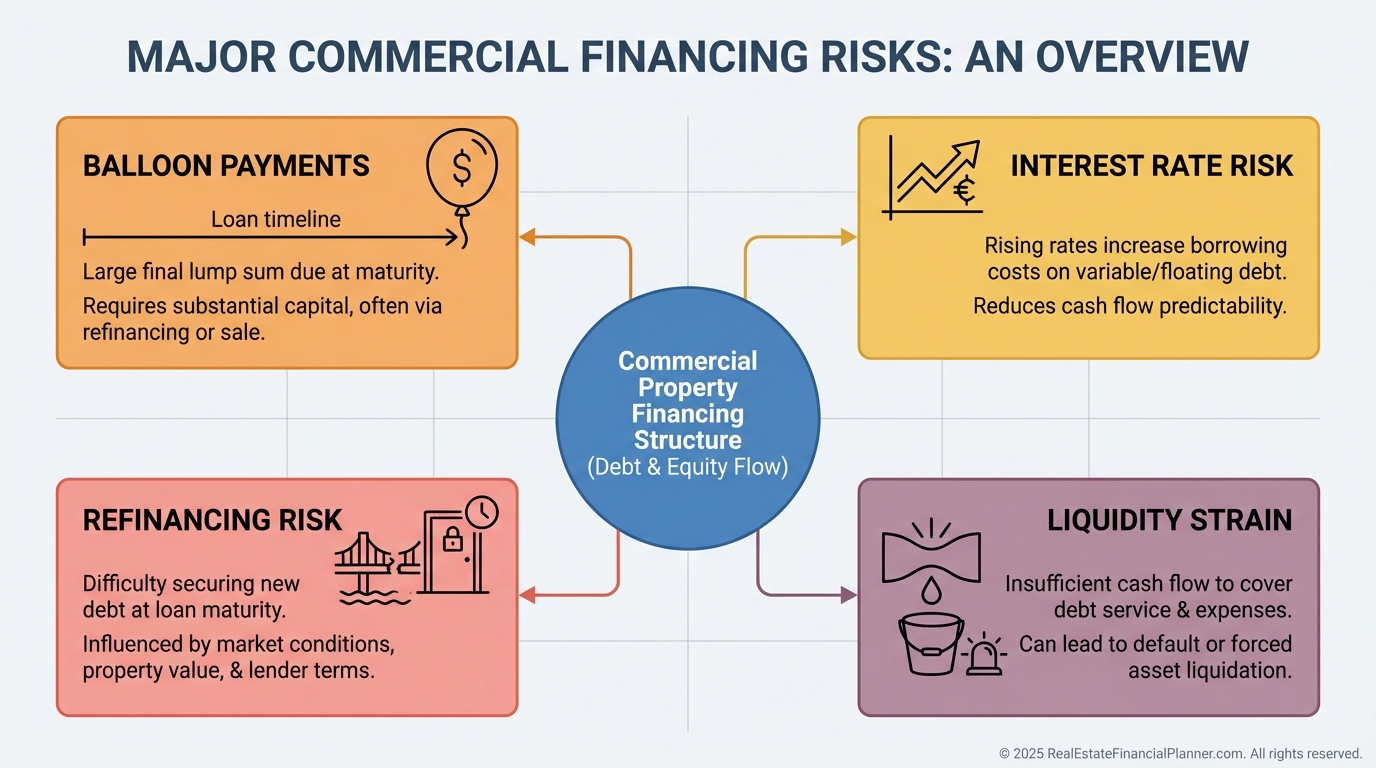

Risks You Must Model Honestly

Commercial financing amplifies both success and mistakes.

Balloon payments create timing risk.

Higher down payments reduce liquidity.

Higher rates compress cash flow.

Key Commercial Financing Risks

When I review deals with clients, the goal is not optimism.

The goal is survivability.

Commercial financing rewards investors who plan several moves ahead and punishes those who assume best-case outcomes.